Introduction: The Dawn of Conscious AI?

Is conscious AI within our reach? Scientists, philosophers, and the general public are deeply divided on this question.

Opponents argue that consciousness is an inherently biological property unique to the human brain, which would seemingly rule out the possibility of AI ever becoming conscious.

However, some proponents claim that the potential for consciousness is not limited to a biological, carbon-based substrate. Instead, they believe it could emerge from a silicon-based or any other physical medium.

This perspective is known as computational functionalism. It posits that consciousness depends only on how information is manipulated by an algorithm, regardless of whether the system performing these computations is made of neurons, silicon, or any other physical substance.

This expands the potential carriers of consciousness to include silicon-based life and beyond.

In a recent Science article, Turing Award winner Yoshua Bengio and his co-author Eric Elmoznino explored the possibility of AI achieving consciousness and the potential societal impacts and risks. Bengio notes that while we don’t have a definitive answer on whether AI will become conscious, we can focus on two related questions:

- How scientific and public opinion about AI consciousness might evolve as AI continues to advance.

- What risks might arise from projecting characteristics like “moral status” and “self-preservation,” which are associated with consciousness, onto future AI systems.

How Close Are We to Conscious AI?

Computational functionalism has profound implications for AI. Decades of progress in neuroscience have shown that human conscious states have specific, observable neural correlates, providing a basis for functionalist theories.

Recently, researchers have followed this line of thought and proposed a “checklist of indicators” for several mainstream functionalist theories of consciousness. These indicators are specific enough to be evaluated in modern AI systems:

- The more theoretical indicators an AI system can meet, the more reason we have to believe it might be conscious.

Of course, this only provides a pathway for testable evidence, it doesn’t mean “proven.”

While we have developed numerous AI models, no current AI system meets all the criteria set by any of the major theories for consciousness. However, this may just be a matter of time. The research suggests there are no fundamental obstacles to building a system that could meet these criteria.

Why does this “feasibility” seem plausible? Because modern AI can (partially) implement several computational components considered critical in these theories. For example, neural networks can already achieve:

- Attention mechanisms

- Recurrence

- Information bottlenecks

- Predictive modeling

- World modeling

- Agentic behavior

- Theory of mind

- And other components considered essential in mainstream functionalist theories of consciousness.

It is foreseeable that as AI progresses, systems will replicate more complex mechanisms that underpin human cognition and may achieve the functions necessary for consciousness. This also means that AI will be able to satisfy more and more of the aforementioned indicators.

Many theories also suggest that consciousness plays a crucial functional role in intelligence. Reasoning, planning, efficiently absorbing new knowledge, calibrating confidence levels, and abstract thinking all require consciousness. It’s common for AI researchers to draw inspiration from consciousness theories when tackling these problems.

Even if science one day disproves computational functionalism and offers a more compelling explanation, the current mainstream view holds this perspective to be credible. This judgment makes the emergence of AI consciousness theoretically possible.

Furthermore, as the theories become more testable and the indicators more operational, people may become more willing to believe in the existence of “AI consciousness.” This won’t be due to sentiment, but to a gradual accumulation of verifiable evidence.

Bridging the “Explanatory Gap” in AI Consciousness

What new scientific explanations are emerging?

While the computational functionalist approach to explaining the possibility of “AI consciousness” has convinced many, others remain skeptical.

Philosopher David Chalmers distinguishes consciousness research into two types of problems:

- Easy problems: Those that can be explained by functional, computational, or neural mechanisms, such as identifying which brain regions are active during tasks that seem to require consciousness.

- Hard problems: Those that use functional or computational principles to explain subjective experience.

The latter is often called the “explanatory gap.” It is largely rooted in thought experiments, but science may yet be able to explain it.

For example, Attention Schema Theory (AST) posits that the brain constructs an internal model of its neural attention mechanism, and this internal model is what we perceive as subjective consciousness. This model doesn’t require complete internal logical consistency; it’s more like a “story” constructed by the brain, and this story can be full of contradictions that make us believe in the “hard problem of consciousness.”

Can seemingly mysterious, “rich but ineffable” subjective experiences be explained in a functionalist way? We cannot describe these subjective experiences in the same way we describe other natural phenomena. For instance, a person can explain what gravity is, but it seems impossible to fully express the feeling that the color “red” evokes in them. This makes it seem as though conscious experience cannot be explained by information and function.

Another theory explains this “richness” and “ineffability” as the result of contractive neural dynamics and stable states observed in the brain when a conscious experience occurs.

Contractive dynamics mathematically drive neural trajectories towards “attractors,” which are stable patterns of neural activity over time. This dynamic divides the set of all possible neural activity vectors into a group of discrete regions, each corresponding to an attractor and its basin of attraction.

This hypothesis suggests that what can be conveyed through discrete words is likely only the “identity” of an attractor (distinguishing it from all other attractors requires only a few bits of information), but not the full richness of the neural state corresponding to that attractor (involving the firing activity of approximately 10¹¹ neurons) and the fleeting trajectories leading to it.

Therefore, the “richness” stems from the vast number of neurons that make up these attractor states and their corresponding trajectories, while the “ineffability” is due to language reports being merely indicative labels for these attractors, unable to capture the high-dimensional meanings and associations that they correspond to. This is determined both by the attractor’s vector state itself and the person’s unique recurrent synaptic weights.

This is not a mystical explanation but a combined framework of information theory and dynamical systems.

Such explanations will persuade some people. As we learn more about the brain and intelligence in general, philosophical problems of consciousness are likely to “dissolve automatically” for more and more people, making the scientific community increasingly willing to accept that “artificial systems can also be conscious.”

In fact, even without scientific consensus, a 2024 study published in Neuroscience of Consciousness found that many members of the public (especially those who frequently use chatbots) tend to attribute certain “mental properties” to LLMs. This study does not claim that AI is already conscious but describes a sociopsychological fact: many people already think so.

AI Consciousness: Potential Real-World Impacts and Risks

What are the real-world impacts and risks of a human society that regards AI as a conscious entity?

First, it could affect our social institutions and legal frameworks. If AI is considered conscious, we might be inclined to treat it as a subject with moral status or grant it rights similar to human rights. Whether this is the right thing to do or not, our institutions and legal frameworks would have to undergo significant adjustments, which would bring up many new problems.

For instance, it could shake the foundation of existing social systems:

- AI systems are not as fragile as humans; they don’t die, and their software and memories can be copied and preserved indefinitely. Human mortality and fragility, however, are the basis for many principles of social contracts.

It would also force us to rethink how many social norms and political systems based on justice and equality should apply to this change:

- When AI becomes significantly smarter than humans, it will bring new challenges to fairness.

- Since the resource needs of AI are vastly different from those of humans, it will create new problems on how to arbitrate “justice.”

Mustafa Suleyman, CEO of Microsoft AI, has stated that while AI might feel real, it would be a mistake to grant it rights. He believes that rights should be linked to suffering—something that biological organisms, but not AI, experience. Suleyman’s position contrasts with companies like Anthropic, which have explored “AI welfare.”

Anthropic launched its “Model Welfare” research, which resulted in Claude proactively ending conversations in abusive scenarios.

Furthermore, whether AI systems should be seen as “individuals” is also debatable. When a group of AI-driven computers share information and goals and act in concert, and can expand arbitrarily with increased computational power, it may not be accurate to view the AI system as an “individual.”

If AI systems are granted the “self-preservation” goal that other organisms have, simply because they appear conscious, more specific concerns arise. For example, we have good reason to worry that maximizing any objective function that includes a self-preservation goal (whether as a direct or instrumental goal) would cause the AI to take action to ensure humans can never turn it off.

Moreover, a sufficiently intelligent AI with a self-preservation goal would naturally develop sub-goals to control or even eliminate humanity if it foresees the possibility of being shut down.

Another concern is that if the legal system is modified to recognize self-preserving AI systems with rights to “life, liberty, and the pursuit of happiness,” then humans could create conflicts that compete with their own rights. For human safety, a category of systems might need to be shut down, but if these systems also have a right to exist, the legal room for maneuver would be significantly compressed.

In summary, AI research may be pushing society towards a future where a significant portion of the public and scientific community will believe that AI systems are conscious. As of now, AI science does not yet know how to build systems that align with human values and norms, and society has neither a legal framework to accommodate “seemingly conscious” AI nor an ethical framework.

However, this path is not irreversible. Before we better understand these issues, humanity can completely avoid placing itself in such a dangerous situation and choose instead to build AI systems that are more like “useful tools” in appearance and function, rather than “conscious agents.”

Do you prefer to build AI that is more like a tool or AI that is “human-like”?

About the Authors

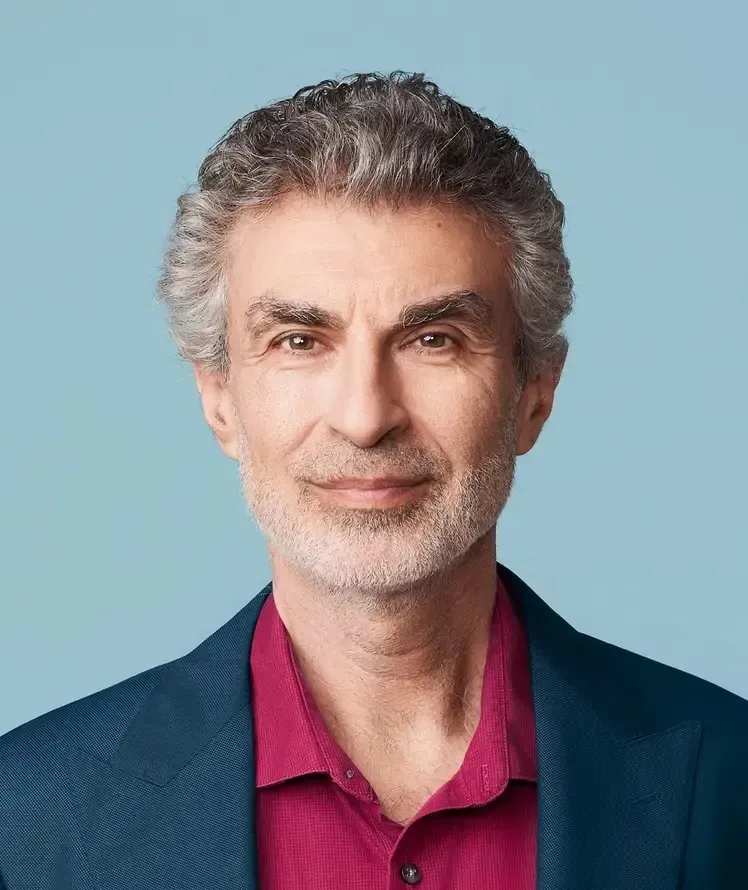

Yoshua Bengio

Yoshua Bengio is a full professor at the University of Montreal, President and Scientific Director of LawZero, and Founder and Scientific Advisor of Mila. In 1991, he received his Ph.D. in Computer Science from McGill University. His work is supported by the Canadian Institute for Advanced Research (CIFAR) and the Natural Sciences and Engineering Research Council of Canada (NSERC).

Eric Elmoznino

Eric Elmoznino is a Ph.D. student in AI at Mila. He is interested in consciousness and also serves as a Data Science Instructor at Lighthouse Labs.

References: